315th Bomb Wing

The following is from the 315th Bomb Wing (VH) history book. It was researched and written by Major Ralph Swann as partial fulfillment of his requirements for graduation from the US Air Force Command and Staff College. It is "Adapted from Air Command and Staff Research Report 862460 entitled A Unit History of the 315th Bomb Wing, 1944-1946."

THE PACIFIC THEATER

War is hell, but it is double hell in the skies.

- Gen. Frank Armstrong

The Early Months on Guam

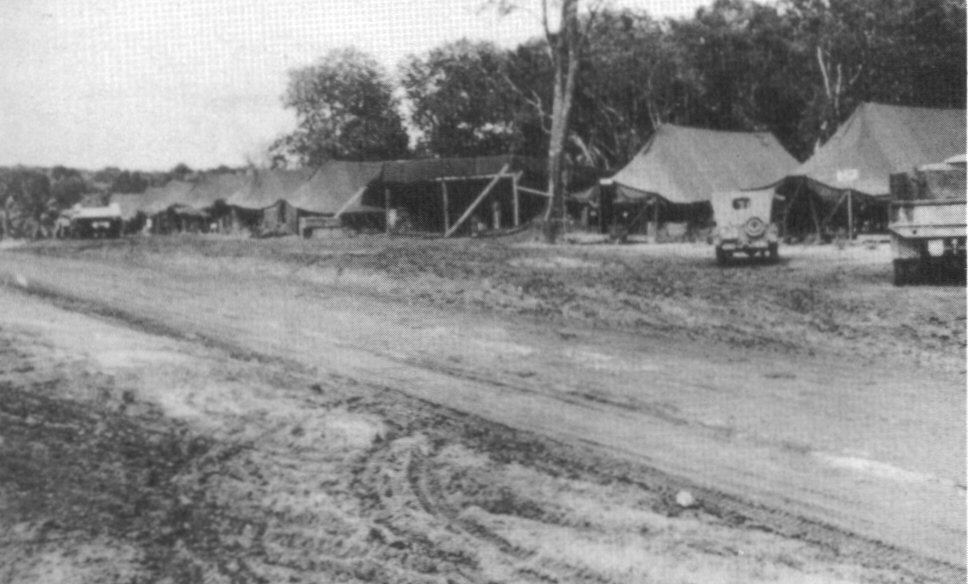

By mid-April 1945, ten Army Engineer and Navy Seabee construction battalions were struggling to complete the airstrip at Northwest Field. Construction officials had underestimated the task in early March and assigned three more battalions to supplement the seven already on the job. The engineers worked around-the-clock to change near impenetrable jungle into an airfield that met the special operational requirements of the very heavy B-29 bomber.

Bases to hold B-29s, however, must be constructed with a firm rock base and a paved surface. When a 135,000-pound airplane lands on the airstrip, three feet of compacted rock base are needed to hold it. To operate successfully under combat conditions the Superfortress should have a runway approximately two miles long and 500 feet wide. There must be parking facilities, dozens of miles of taxi space, and hundreds of hardstands, all of which also must be paved. The approaches have to be free of mountains and other obstacles for 15 miles at each end of the runway. And, instead of moving 30,000 cubic yards of earth (for typical European airfields with medium bombers), it is often necessary to move a million cubic yards of ground.

The hard coral rock lying beneath the jungle growth dramatically slowed the construction pace. The engineers used dynamite, jack-hammers, and bulldozers to loosen, move, and replace the stubborn coral in a valiant effort to meet the scheduled 1 June operational date for the airfield.

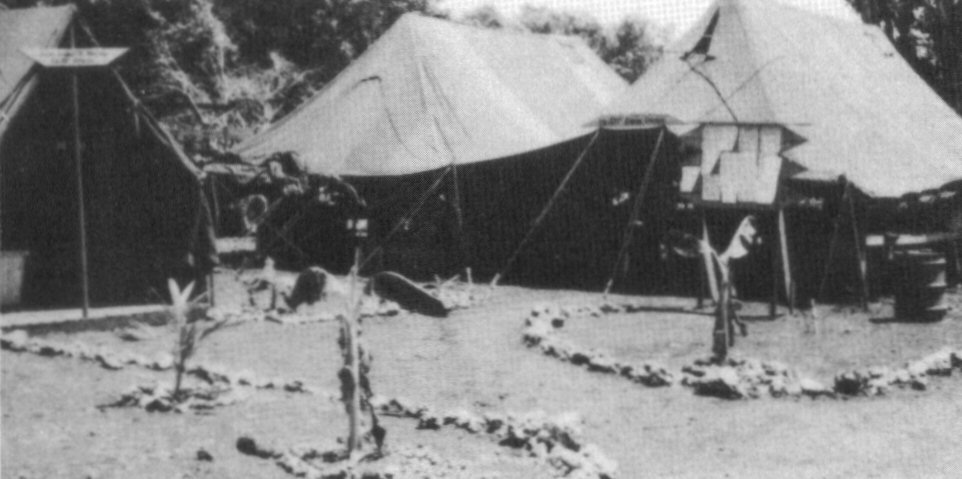

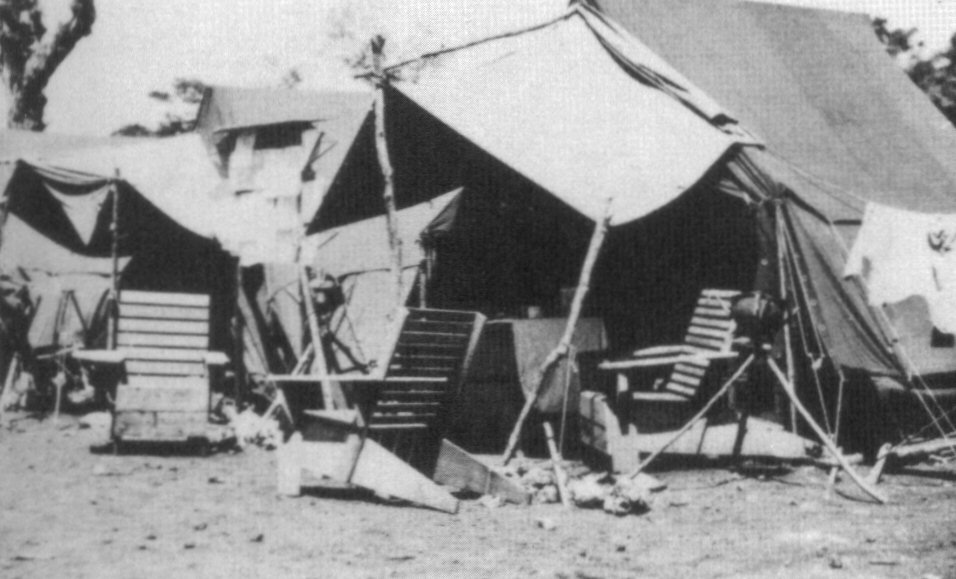

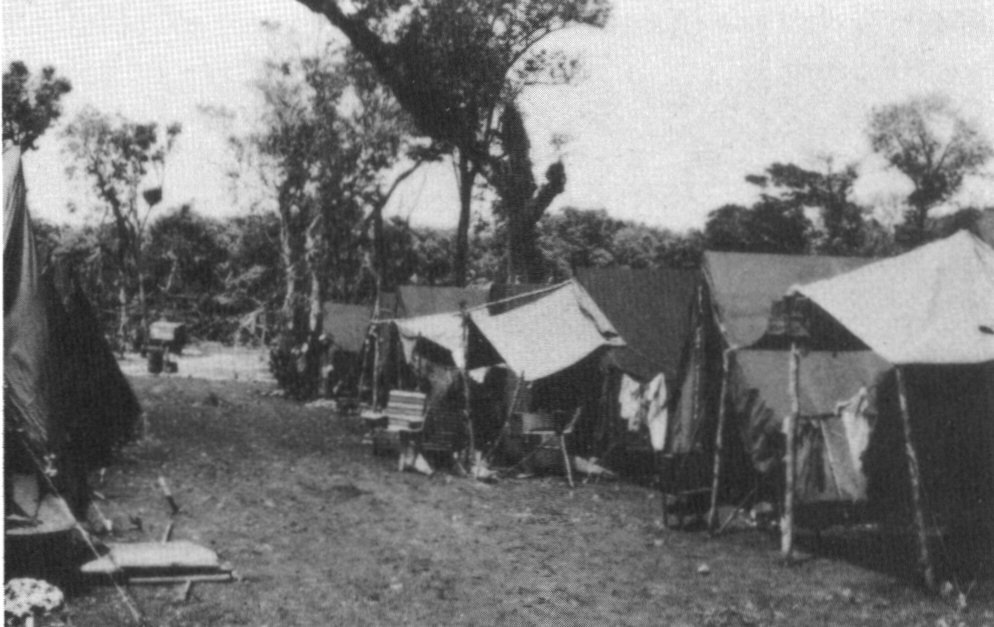

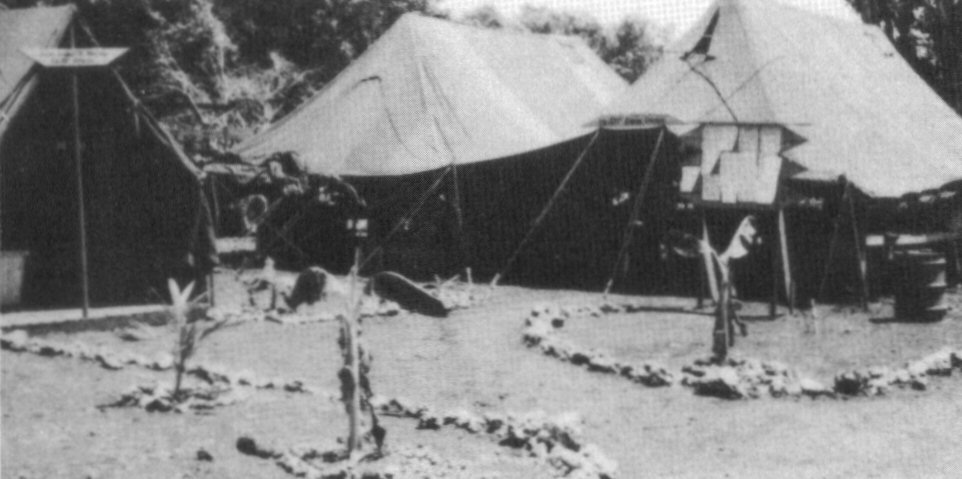

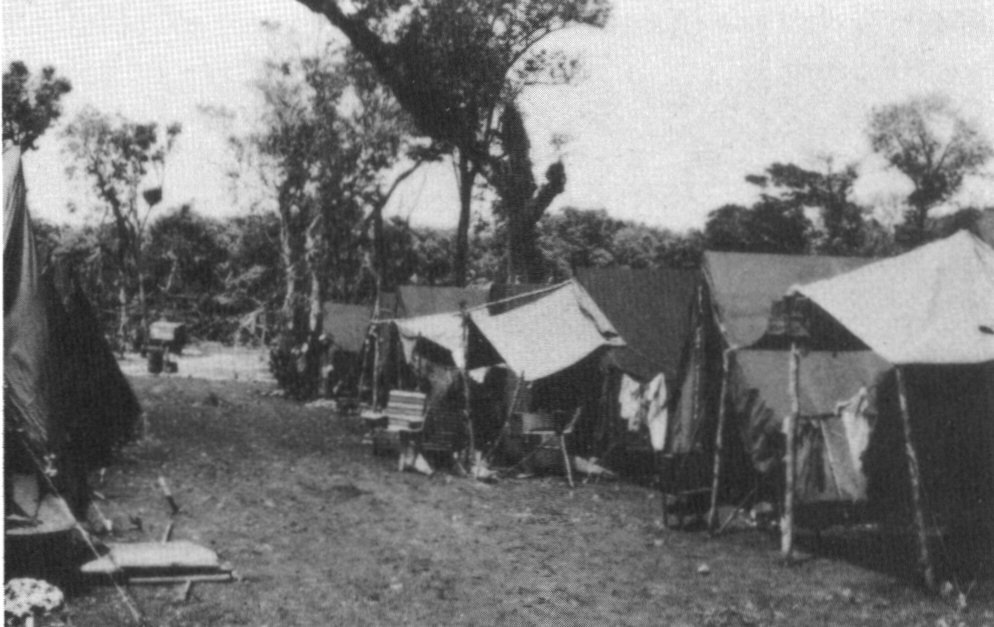

When the wing's first ground echelons arrived at Northwest Field on 14 April 1945, they found very primitive living conditions. The wing had been assigned the last available piece of property on the northwest coast of Guam overlooking a sheer cliff that dropped to the sea. Bulldozer crews had cleared part of the airfield's living areas from the jungle just prior to their arrival. Consequently, there were no living quarters, mess halls, or bathing facilities. There were only a few latrines blasted out of solid coral and a limited supply of water for drinking or bathing in homemade washstands. Temporary living quarters consisted of two-man pup tents and bedrolls on the ground.

The officers of the [76thASG] were not so fortunate, for their bedrolls were not unloaded from the ship, and they did not have their tents for the first night. The officers had to improvise their own shelter from raincoats and palm branches. Few of the officers will forget their experience during the first night trying to keep dry in their makeshift shelter during the incessant downpour.

The men ate C-rations during the first week. Later, field ranges were uncrated and used to heat the C-rations. The throng of insects, lizards, and huge rats which lived in the nearby trees added to their discomfort.

On their first night on Guam, Privates Harry H. Abernathy and Herbert E. Rowsey were assigned to guard duty and had an uninvited guest. Although Guam had been secured by American forces on 11 August 1944, an unknown number of Japanese soldiers were still hiding on the island in 1945. Thus, Abernathy and Rowsey were picked to patrol the L-shaped area assigned to the 16th Bomb Squadron from midnight to 0200 hours. Although the men were armed with carbines, they had no ammunition. Suddenly "it sounded like Solomon's Army coming through the jungle." Both men quickly fell to the ground, held their flashlights up at arm's length, and shined the light into the jungle searching for the enemy. The beam of light caught two beady eyes nodding from side to side and coming closer and closer. Suddenly, the enemy came into full view, and the men were face to face with a 3-foot lizard. They guessed it was harmless and, with a sigh of relief, returned to their guard duties.

The water supply was the most critical problem at Northwest Field. Although a deep well with a capacity of 800 gallons per minute was located within 2 miles, the Navy held first priority and wouldn't release a pump to the 315th to use the well. Thus, water had to be hauled 47 miles, round trip, by truck from Agana and chlorinated again prior to use. The water was placed in lyster bags* throughout the area for drinking and in 5-gallon cans for bathing and washing. "The steel helmet became one of the most important pieces of equipment carried by the men and was used for washing, bathing, and washing clothes." Shower facilities were unavailable for seven days until the chemical warfare sections converted two large decontamination trucks into shower trucks. The massive water hauling operation created a logistical and maintenance nightmare for transportation personnel who struggled to keep the wing's water supply lines moving.

[*Lyster bags were portable waterproof bags used to supply disinfected drinking water.]

Local circumstances forced the 315th to construct its own living quarters and office buildings. When the wing's ground echelons arrived, the 1886th and 1887th Engineer Aviation Battalions were the only units available to work on the wing's building facilities. However, these construction units were immediately directed to work on the higher priority Northwest Field airstrip project. Thus, the 315th was tasked to erect its own buildings. Men from the wing headquarters squadron, bomb groups, and service groups were organized into construction crews for locating and erecting the prefabricated barracks and administrative buildings. Living quarters and mess halls had the highest priority while quonset huts and frame buildings for offices were put up based on future wing operational requirements. The men worked long days in a tropical climate drastically different than that at the training bases in the States. Within a few days, the men improved their skills and were soon completing three barracks a day.

The 315th's medical staffs did a remarkable job maintaining satisfactory health conditions. Mess, latrine, and other camp sanitary facilities were constantly inspected. The deep latrine pits were oiled twice and burned out once weekly. Pits were constructed for the disposal of waste and laundry water. Preserving perishable food was a major problem in the tropical climate, thus only a 24-hour supply of perishable foods was kept in refrigerators at the mess halls. The mess halls were screened and fly-proofed by spraying with DDT. Pellets of Red Squill, a rat poison, were distributed throughout the area to control rats. Bathing facilities were constructed, and the water purification process was closely monitored. Finally, the medical staffs distributed informative literature on personal hygiene, preventative medicine, and general health safety procedures. Consequently, the only widespread epidemic was an initial outbreak of diarrhea attributed to an over indulgence in coconut milk and an intestinal influenza brought from the ships.

Every special services section strove to improve morale. The three main factors undermining morale were the primitive living conditions, the long work hours in a tropical climate, and the lack of recreational and post exchange facilities. Each special services section used every possible means to overcome these problems.

On the 15th [in the 501st Bomb Group] plans were underway for the construction of a theater and on the 17th of April the theater was in operation. Bomb Boxes were acquired from ordnance dumps for seats, a small shack was built for a projection house, and a sheet spread-eagled for a screen. On the 17th of April, a small quantity of PX supplies was purchased for resale to the troops. Several days later a temporary PX was set up and items were purchased on a cash-and-carry basis from the Main Island Exchange. Both the theater and the PX were the first to be established as such in the Wing.

Sports fields for softball, baseball, football, volleyball, basketball, and horse shoes were constructed and competitive matches were organized. Sunday church services were initially held in the open air until tent chapels were put up. Each Sunday afternoon the men were allowed to swim at the nearby beaches or to attend boxing bouts at other island installations. The task of maintaining morale was difficult because the base construction activities seemed so far removed from supporting combat operations.

In April, Gen. LeMay decided the 315th would attack the Japanese oil industry. This industry had barely been scratched because it "was not specified as a top priority objective in the current assigned target list." However, Gen. LeMay believed Japan's oil industry was in a critical state and should be knocked out. Moreover, he thought the 315th should strike the refineries because they were located on or near the coastline where the 315th's Eagle radar could pick them up effectively.

Our strength was increasing enormously as new units flew in to join us. The 315th was the last to arrive, commanded by that old Eighth Air Force warhorse, Frank Armstrong. Oil targets became the specialty of the 315th. They were the only B-29 wing equipped with the so-called Eagle radar... .The Eagle had been designed especially for bombardment, and the 315th had trained especially for night missions. This added up to putting them on oil refineries, oil storage facilities, and even synthetic plants.

Lieutenant General Barney Giles, the new Deputy Commander of the Twentieth Air Force, immediately supported Gen. LeMay's decision. When queried by Washington, General Carl A. Spaatz, Commander of the U.S. Strategic Forces Europe, also strongly supported the decision because he had seen the German war machine grind to a halt following the strategic bombing campaign against Germany' s oil industry. In addition, the Strategic Intelligence Section of the Air Staff in Washington concluded that the destruction of the Japanese oil targets would have an immediate effect upon the tactical situation. Thus, Gen. LeMay's decision was well supported, and the 315th's first objective in the strategic air war was the destruction of the Japanese oil industry.

As a result, the 315th was put under extreme pressure to perform. Gen. LeMay's previous attempts to test selective target bombing using the APQ-13 radar had proved inadequate. Now the 315th, with its highly touted Eagle radar, was given "the opportunity to test again the feasibility of all- weather attack against selected targets and at the same time to make a substantial contribution to the conduct of the war." Since Japan's oil industry was practically intact, it provided an excellent target to evaluate the 315th's performance. Thus, the 315th was under the gun to prove its radar bombing accuracy.

Meanwhile, the 509th Composite Group was reassigned from the 315th to the 313th Bomb Wing in April. Prior to the 509th's deployment overseas, Colonel Fitzpatrick, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, was sent to the Pacific to find an air base suitable for the special needs of the 509th. His search revealed that Tinian provided the ideal combination of security, runway length, and a remote area to construct an ordnance facility to handle the atomic bomb. In addition, a Naval Seabee unit was available to provide construction support. Since these factors negated basing the 509th with the 315th at Guam, the 509th was assigned to the 313th Bomb Wing at Tinian.

Moreover, the Twentieth Air Force was also reorganized in April. The four bomb groups assigned to the XX Bomber Command and based on Tinian. However, the headquarters for Twentieth Air Force remained in Washington, D.C.

On 11 and 12 May, the 315th's remaining ground echelons arrived at Northwest Field and found the living conditions somewhat better than their predecessors had in April. The 24th and 75th Air Service Groups arrived on 11 May, and all personnel, except the 581st and 587th Engineering Squadrons, were assigned to quarters on the southern side of the airstrip. The 581st and 587th were assigned to the less developed northern side of the airstrip along with the 331st and 502nd Bomb Groups' ground echelons which arrived the following day. Two-man wall tents and latrines were ready and waiting. Showers were available although water was still in short supply and strictly rationed. The men dined on C-rations because their mess halls were still a week from completion. Fortunately, mail was distributed in the evening, and it helped the men temporarily forget about the long sea voyage and conditions at Northwest Field.

The 315th's eight photographic units were consolidated into one organization after their arrival at Northwest Field. Prior to deployment, each bomb group and services group had its own photographic section operating independently of the wing and each other. The 315th's photographic officers believed this system would prove inadequate under operational conditions particularly if the separate units were widely scattered at Northwest Field. Thus, during the voyage to Guam, photographic officers from the wing headquarters and the 16th and 501st Bomb Groups proposed a plan to consolidate all photographic units into one organization to meet the operational needs of the wing. These plans were implemented immediately at Northwest Field with the construction of an H-shaped wing photo lab near the wing headquarters building. However, the photographic units weren't the only units to be consolidated.

The wing's four service groups were the victims of a B-29 base reorganization plan initiated by XXI Bomber Command. The plan originated to deal with the unique wing basing system and logistical shortages in the Pacific theater. Due to the limited land mass available in the Marianas, individual wing bases were established to house over 12,000 men and provide facilities for over 180 B-29s. The wing headquarters was established as the dominant operating entity responsible for the tactical, logistical, and maintenance activities of the four combat groups and four service groups at its base. Naturally, the massive buildup of B-29 forces in the Pacific led to critical shortages of manpower, equipment, and supplies and it became necessary to economize operations. Thus, each wing was directed to combine the supply and maintenance functions of its separate service groups to form centralized wing functions. This meant the integrity of the service groups was sacrificed for economy and efficiency to meet wing requirements.

As a result, the 315th's four air service groups (ASG) began to consolidate their activities in April and May to form a single wing service center. The 315th Wing Headquarters directed the ASG's to consolidate their respective sections along functional lines to conserve manpower and improve efficiency in support of wing operations.

Suffice to say, it was very detrimental to the morale of the officers and men who had worked and trained hard with their friends and associates. Immediately, we had four of everything: commanders, adjutants, personnel staff, enlisted sections chiefs, etc. In some cases, men were selected as assistants to someone junior to them. Also, some were assigned as assistants to assistants. This also resulted in a surplus of officers and men in some departments, so many of them were called upon to perform tasks far removed from their military specialty. Morale was at a low ebb.

Col. Neyer, the 75th ASG Commander, was the senior ASG officer and assumed command of the wing service center. He immediately initiated a series of administrative actions to implement the reorganization guidance.

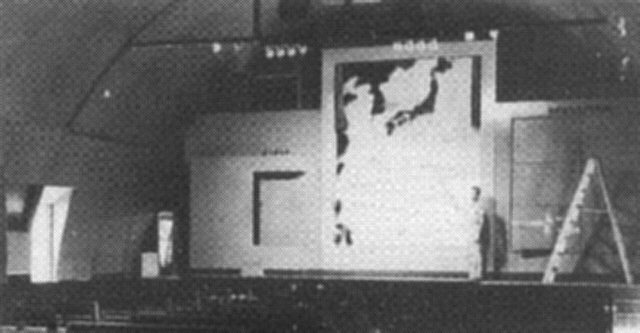

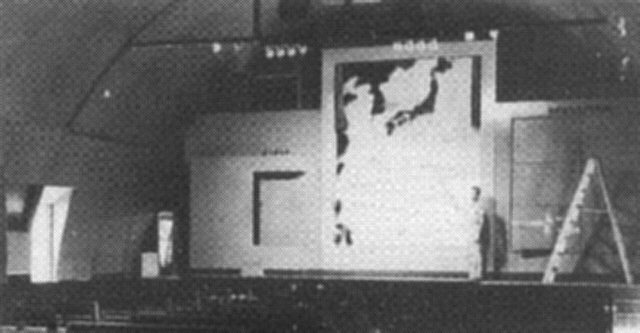

The 315th planned to incorporate a unique visual display technique into the wing briefing room at Northwest Field. Prior to deployment overseas, the 315th Headquarters, air echelon at Peterson Field had initiated a project to find a better means of presenting briefing data to flight crews. Current briefing systems relied on poor quality visual projection machines such as the Baloptican and Epidiascope. Thus, the air echelon began an extensive series of tests with phosphorescent and luminescent paints and ultraviolet light.

Using these materials, it was found that the briefing personnel could project pictures, maps, radarscope photographs and charts so clearly that crews could gain a more rapid and lasting understanding. Specific points of interest could be emphasized in more prominent relief through the use of different colors. Another method involved the employment of paints which are invisible under ordinary electric light, but which appear quite prominently under the ultraviolet illumination.

The results of these tests were submitted to Higher Headquarters, and the 315th was granted permission to use the new method overseas. Thus, the wing briefing room's interior was designed to display large data boards utilizing the new illuminated briefing technique.

Six radarscope photographic missions were flown in May. Radarscope photography was a new development using a special camera, the 0-5, attached to the Eagle's radar machinery to record the images displayed on the radarscope. The radarscope film was used for crew briefings and to help operational planners. The missions in May were flown to obtain radarscope film for later use by the 315th in combat mission planning and to provide training materials for the flight crews still in the States. The first mission was flown on 5-6 May by Capt. Howard's crew in the "Elite Barbara and Her Orphans." The crew took off from North Field, Guam, where they had been temporarily attached to the 314th Bomb Wing pending completion of Northwest Field's runways. The mission was flown over the Kawasaki Aircraft Plant near Nagoya on the main island of Japan. The crew encountered no flak, but a Japanese fighter trailed the B-29B for 100 miles out to sea. Capt. Howard's crew flew five more missions during May to Kobe, Osaka, Tokyo, Yokohama, and Tamashima. Col. Gumey, the 16th Group Commander, flew with Capt. Howard's crew on the 31 May mission to Tamashima. Most missions were flown at 15,000 feet and the radarscope photographs obtained ranged in quality from good to excellent.

Maj. Tintensor's crew and aircraft, "Roadapple," were lost on the 8 May radarscope mission to Kobe. The crew were members of the 21st Bomb Squadron. They took off from North Field with Capt. Howard's crew on the daylight mission but failed to return. The reason for the loss of the five officers, five enlisted man crew was unknown. However, Capt. Howard's crew suspected aircraft icing as a possible cause since they had also experienced difficulty with icing on their aircraft.

NOTE: A report from Japanese documents published after the war, show that "Roadapple" was shot down by anti-aircraft fire over Osaka, Japan. (lm)

On Sunday, 24 May 1945, the 502nd Bomb Group conducted a special flag-raising ceremony. The unofficial ceremony began at 0630 hours when the men were marched to the main square of the group's ground echelon area. Around them stood rows of two-man tents erected earlier in the week as their temporary homes on Guam. Four group officers presented an American flag to Colonel Joyce, commander of the ground echelon, who ordered the raising of the nation's colors. First Lieutenant Godsell, Group Special Services Officer, led the entire group in singing the National Anthem as the American flag fluttered in the morning breeze. This ceremony occurred six weeks after the 502nd's ground echelon left Grand Island, Nebraska, and marked the end of their period of initiation on Guam. The group was ready to begin constructing its permanent home and preparing for full-scale combat operations at Northwest Field.

Later that day, four enlisted men from the 485th Bomb Squadron, 501st Bomb Group, were envolved in a tragic accident. The accident occurred around 1900 hours as the men were proceeding toward the Northwest Field housing area. Along their route of travel, a bulldozer had previously punctured an aviation gas pipeline on the side of the road causing gas to be sprayed onto the roadway. When the weapons carrier carrying the men entered the affected area, the gasoline fumes ignited and all four men were seriously burned.

As a result of [their] burns, Pfc. McCarty died at 2357 hours on 24 May 1945; Pvt. Barna died at 0300 hours, 26 May 1945; Pfc. Lantosh died at 2300, 25 May 1945; and Pfc. Phillips died at 1500,26 May 1945. Pfc. Phillips was buried at Military Cemetery number two, Guam. Pfc.'s McCarty and Lantosh and Pvt. Barna were buried in the same cemetery on 27 May 1945.

The loss of these men reminded their comrades of the dangers of fighting a war, regardless of one's location in the combat zone.

The 315th Wing Headquarter's air echelon arrived on Guam between 20 and 28 May. The air echelon came in small groups aboard a stream of 315th B-29Bs. Gen. Armstrong arrived on 28 May in his own B-29B, the "Fluffy Fuz III," built especially for him by the Bell-Marietta Company in Georgia. The "Fluffy Fuz III" had the normal B-29B modifications plus fuel-injection engines and reversible propellers which allowed the aircraft to use only half of the runway when it landed on Guam. The next day, 29 May 1945, Gen. Armstrong assumed command of the 315th Wing Headquarters at Northwest Field.

On 1 June, a formal dedication ceremony for Northwest Field was held on the south runway. Gen. Armstrong circled the field in his "Fluffy Fuz III" to begin the ceremony and landed on the newly completed south runway. He taxied the aircraft and parked facing the distinguished visitors' ceremonial platform while hundreds of men from various military services responded with thunderous applause and cheers.

On the speakers' platform with the Naval executive (Admiral of the Fleet Chester W. Nimitz) were.'Lt. Gen. Barney M. Giles, commanding the Army Air Forces in the Pacific Ocean Areas; Maj. Gen. Curtis E. LeMay, Commanding General of the XXI Bomber Command; Maj. Gen. Henry L. Lorson of the Marines, the Island Commander; Brig. Gen. Frank A. Armstrong Jr., Commanding General of the 315th Wing; and Col. Lee B. Washburn, Commanding Officer of the 933rd Engineer Aviation Regiment, the construction director.

The distinguished speakers highlighted the significance of the event in the brief but impressive ceremony. Admiral Nimitz, the honored guest for the occasion, made the opening ceremonial remarks. He commended the aviation engineer and naval construction battalions for their superhuman efforts to build NorthwestField. He also stressed the connection between the mission of the troops on Guam to the total war effort in the Pacific. Col. Washbum spoke next and declared Northwest Field operational. Gen. Armstrong promised a fine flying tradition and excellent results from the 315th's future combat operations out of Northwest Field. Gen. Larson spoke of the "unity of command and purpose" in this construction project and concluded by saying Northwest Field was a "milestone in the march to Tokyo." Finally, Lt. Gen. Giles also commended the engineers and revealed that certain ranking Japanese engineers had told the Japanese Imperial Command that insurmountable terrain problems would never permit American B-29 forces to operate out of the Marianas. Gen. Giles then wondered what these Japanese engineers would say after the upcoming B-29 Superfort raids.

In early June, First Lieutenant Wesley Rhodenhamel, 15th Bomb Squadron radar navigator, made a special deal with some Navy Seabees to improve his standard of living. The Seabees came to Northwest Field trying to trade fake war souvenirs for booze. The men in Lt. Rhodenhamel's Quonset hut weren't interested, but he offered 4 quarts of booze for a refrigerator, a luxury item found only at the mess halls. Although the two parries agreed on 6 quarts, Lt. Rhodenhamel didn't expect the Seabees would deliver. Two days later around 0300 hours, four Seabees backed a truck up to the rear of his Quonset, unloaded a refrigerator, and demanded 8 quarts of booze. They settled for 7. The refrigerator was promptly plugged in, stocked with warm beer, and temporarily hidden with a sheet. Before daylight the refrigerator was enclosed in two modified 500-pound bomb crates and resembled the other similarly constructed clothes closets in the Quonset. Later in the day, Lt. Rhodenhamel and a Quonset mate drove to the Navy base at Agana and bought enough fresh lettuce, tomatoes, and cans of Navy hams to make sandwiches for awhile. They also bought a hot plate for only one bottle of booze and set out to procure bread from the mess halls even though this was strictly forbidden by posted official notices. Two days later, notices were posted all over Guam requesting information from anyone "knowing the whereabouts of Admiral Nimitz' refrigerator." The men in Lt. Rhodenhamel's Quonset knew they were in trouble if their tough-minded Squadron Commander, Lieutenant Colonel Richard Kline, ever found out. Consequently, they were extremely cautious thereafter when they drank their cold beer and ate their sandwiches. While they secretly thanked Admiral Nimitz for the refrigerator, the wing was also preparing to formally thank him for his help in other areas.

On 14 June, the 315th held a special dedication ceremony at Northwest Field to honor Admiral Nimitz. Gen. Armstrong wanted the 315th to give special recognition and tribute to Admiral Nimitz and all the naval personnel who had given so much logistical support to build Northwest Field's airstrip. Therefore, the 315th readied a B-29B, named it the "Fleet Admiral Nimitz," and dedicated it to Admiral Nimitz at 1700 hours on Northwest Field's south taxi strip. General H. H. Arnold, who was in the area on an inspection tour, was the keynote speaker for the ceremony. In his remarks, Gen. Arnold referred to the dedicated B-29B as a "distinct manifestation of the gratitude and admiration of the 315th Wing and the entire Air Force for Admiral Nimitz." Gen. Arnold added that Japan would soon feel the weight of what the name Nimitz meant when the aircraft began its combat missions against the Empire. In response, Admiral Nimitz expressed his honor and gratitude for the special christening.

After the official ceremony, Admiral Nimitz and Gen. Arnold inspected the "Fleet Admiral Nimitz." They were introduced to Col. Hubbard, the aircraft commander and 501st Bomb Group Commander, and his crew. Next, Admiral Nimitz and Gen. Arnold toured the aircraft, and the crew described their respective duties and the aircraft's outstanding features. Before departing, Admiral Nimitz presented Hubbard with a five-star insignia to put in the upholstery, a case of beer, and a bottle of Haig and Haig for the crew to celebrate with later." In an expression of good luck, Admiral Nimitz later sent an autographed portrait to the crew members of the "Fleet Admiral Nimitz." The good luck gesture was well timed because the crews were busy training for their first combat mission.

The 315th's flight crews had to complete several weeks of theater indoctrination training before they could fly missions over the Japanese Empire. The training included two days of ground school, two orientation flights, and two shakedown missions required by a special XXI Bomber Command directive. Ground training included target study, air-sea rescue procedures, and tactical doctrine. The local orientation flights prepared crews for operations out of Guam. The two shakedown mission targets assigned to the 315th were Truk and Farajon de PaJaros. Truk, a major Japanese stronghold in the Eastern Carolines Islands by-passed by advancing American forces, still had Japanese forces on it and provided an excellent training target. Pajaros was a totally uninhabited and militarily unoccupied island in the Marianas used for bombing practice. The shakedown training included a trip to Iwo Jima, a small but vital B-29 emergency airfield secured at a high human cost by American Marines.

The first of seven shakedown missions for the 16th and 501st Groups in June was flown on the night of 16 June. Gen. Armstrong attended the pre-mission briefing. He welcomed the crews to the combat area and congratulated them on the start of their combat careers. He warned them that "war is hell, but it is double hell in the skies." He also urged caution until they gained combat experience. Twenty-six crews flew the first practice bombing mission to Moen Island, Truk, and the mission was successful. The two groups flew six more shakedown missions on 21,23,25,27, 28, and 30 June to Moen Island and Pajaros. Although there were no losses due to enemy action, one B-29B crashed during landing following the 28 June mission to Truk. Fortunately, the crew survived the accident.

The flight crews practiced their defensive measures on these relatively safe shakedown missions. They were authorized to go to full power and top speed in their B-29Bs to evade enemy fighters, searchlights, and flak. In addition, pieces of aluminum foil, or "rope," were also ejected over the target area to confuse enemy radar-controlled search-lights. If the rope was dropped too late, the aircraft could be lit up, or "coned," by the searchlights, and the antiaircraft batteries could zero-in for the kill. Finally, the crews depended on the APG-15 tail turret guns as their only defensive firepower against fighter attacks. Despite these defensive measures, the 315th's crews were excellent targets in their lightly armed Superforts flying in a single-ship stream over the target.

While some crews were flying shakedown missions in June, other crews were flying radarscope photography missions. Usually one or two aircraft were sent on these missions to obtain radar film of Japanese oil industry targets. During the month, "such priority strategic sites as the Utsube River Oil Refinery, the Kawasaki Petroleum plant near Yokohama, the Ube Coal Liquefaction works at Kudamatsu, the Maruzen refineries and others were photographed extensively." The wing's operational planners analyzed the radar-scope film for the wing's upcoming strikes against Japan's oil refineries. These missions also helped the radar and photo technicians to eliminate any remaining discrepancies in the radar and camera equipment. However, these weren't the only last minute preparations for the wing's first combat strike.

A new air-sea rescue (ASR) system was implemented during June. Under this system, an LCI (landing craft, infantry) would patrol the shoreline of the island just off the runways when the Superforts started their Empire missions. In addition, a Dumbo (rescue aircraft) would cruise over the shoreline area to direct the LCI to any aircraft and crew in distress. Subsequently, the flight crews were required to practice ditching drills using this new ASR system. Each crew was taken a few miles out to sea in an LCI and tossed overboard with only a Mae West (life vest) for floatation. Shortly thereafter, a Dumbo dropped a rubber raft to the crew who inflated the raft and then used a signaling mirror to contact the Dumbo. The Dumbo contacted the LCI and directed it to pick up the crew. This local ASR system was part of an elaborate system set up in the Pacific using submarines, destroyers, and long-range patrol search planes to support downed aircrews. Although the flight crews hoped they would never have to use the ASR system, it was reassuring to know it was there as they crossed the vast Pacific.

On 18 June, a large service center theater was dedicated and named "El Gecko." The theater's name. El Gecko, was the Guamanian name for a common, harmless lizard on the island. The dedication ceremony capped many hours of voluntary off-duty labor performed mainly by service group personnel. Navy Seabees and Army Engineers supported the effort by bulldozing and terracing the building site. A large stage, 40 feet by 90 feet, was built to attract live entertainment to the 315th's pan of the island. Theater-like seats were constructed from discarded wooden bomb crates. The huge outdoor amphitheater had a seating capacity of over 5,000 and provided an excellent facility for presenting live stage shows and movies. The El Gecko theater was one of the finest entertainment facilities on the island, but it wasn't the only source of recreation.

In June, five enlisted men went searching for war souvenirs and found more than they wanted, some were still alive. Initially, Harry H. Abemathy, Harry J. Edwards, John C. Hockaday, Charles E. Ohse, and Cecil G. Westberg were lucky and found a Japanese skeleton and a broken trench shovel in the jungle. They continued their search through a coconut grove where the surrounding savannah grass was head high.

About that time three Japs jumped across the trail and we could see the rifles and the hand grenades they were carrying. I (Abemathy) do not know who was the more frightened, the Japs or us. Anyway, Hockaday and Westberg wanted to fight them barehanded, and Edwards and I said it was time to return for supper. This was about 3 p.m. and we both knew supper was not ready until several hours later. About that time, Edwards, Ohse, and I started to run, and a bang came from somewhere and Westberg and Hockaday ceased yelling to come out and fight barehanded and ran with us. I do not know if any other men of the 16th Sq., 16th Gp. ran from the enemy, but we five certainly did.

Encounters such as this were rare since the Japanese soldiers preferred to hide in the jungle, and many of the men in the 315th weren't as adventurous. Fortunately, these men escaped with a lifelong war memory and didn't become the enemy's war souvenirs.

On Saturday, 23 June 1945, the 331st and 502nd Bomb Group Commanders arrived at Northwest Field. The aircraft bearing Col. James Peyton, the 331st Commander, was greeted by four jeep loads of men led by Lieutenant Colonel George B. Mackay, commanding officer of the group's ground echelon.

Colonel Peyton - Arrival Guam

An airman dropped through the plane's nose wheel well, flashed a grin at the welcoming committee, greeted Lt. Col. Mackay, 'George, that ocean's big!' Col. James N. 'Big Jim' Peyton, Commanding Officer of the 331st Bombardment Group, had arrived. With him, 6,000 miles and 28 Superfortress hours from the U.S., was the group's first combat crew to reach the unit's operational base, a 356th Squadron crew led by Captain Julius H. Baughn.

That same day, a plane piloted by Col. Kenneth O. Sanborn, the 502nd Commander, touched down on the south runway. A few minutes later, Col. Joyce welcomed Col. Sanborn, Major Ronald Johnson (502nd Group Technical Inspector), and Captain Dillingham's flight crew to Northwest Field. The ground and air echelons of both bomb groups were glad to finally be reunited.

Colonel Sanborn - Arrival Guam

The 315th wing staff gave construction priority to Service Center G during June. Service Center G was located on the southern side of the Northwest Field airstrip and was the designated operations area for the 16th and 501st Bomb Groups. The 331st and 502nd Bomb Groups were scheduled to use Service Center H following its construction on the northern side of the airstrip. Since the 16th and 501st were scheduled to become operational first, the large (75 structures) Service Center G complex received the highest construction priority. By the end of June, 68 of the 74 structures were finished with the remaining 6 nearly completed. In contrast, none of the 54 structures planned for Service Center H were begun in June.

Several of the 315th's key facilities were completed just in time for the wing's first combat mission. The wing briefing room was finished, and its walls were lined with large panels to provide aircrews with the latest information on target statistics, flak defenses, escape and evasion, and strike and reconnaissance photographs. The control room in the new communications building was the central operations communications point for the wing and had enlarged panel boards to show aircraft status, weather data, crew availability, and pertinent flight statistics. The photo lab personnel had radar photographs ready for the pre-strike briefings and were standing by to process post-mission radarscope film to analyze bombing damage. The permanent control tower replaced the temporary one built in May, and the tower personnel were anxious to launch the wing's aircraft on the first combat strike.

Back to Introduction

Back to The Service Groups

On to Operations

Content ©2003-2004, Larry Miller

ljmiller at charter dot net

August 9, 2005